This is an updated version of an article originally published in May 2019.

“Ask not what Trans-Dniester can do for you – ask what you can do for Trans-Dniester.”

We’re driving down Andriy Smolensky’s favourite street. It’s the only one in Tiraspol that doesn’t cause his Land Rover to bounce and rattle over potholes and broken concrete.

“They’ve used a new technology to make it like this,” he says, almost proudly. “I could drive up and down it all day.”

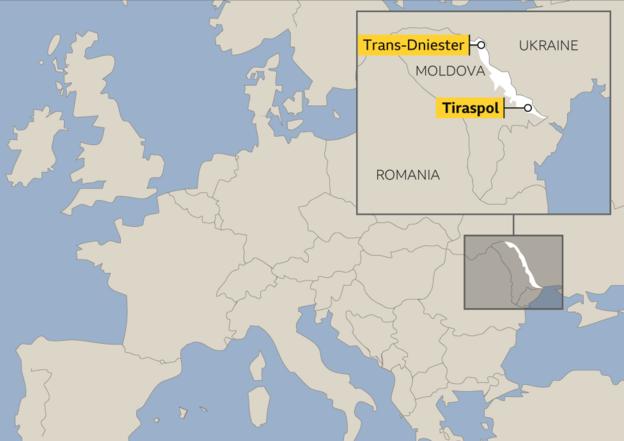

The tiny de facto republic of Trans-Dniester – sometimes known as Transnistria – is a place frozen in time.

In its capital Tiraspol, the hammer and sickle motif of the former USSR is proudly displayed on billboards and government buildings. A huge statue of Lenin looks on from a plinth outside parliament, a mark of the pride and nostalgia the city feels for its Soviet past.

But on Wednesday night, it will take a giant stride towards its future. The city’s football club, FC Sheriff Tiraspol, qualified for the Champions League group stage for the very first time with a play-off victory against Dinamo Zagreb in August. Their reward is a…